By Italy specialist Shannon

I’ve always been drawn to Italy’s places of worship because of the stories of controversy and intrigue hidden in their elaborate sculptures, paintings and façades.

For my Art History degree, I studied in Florence and attended lectures in churches and basilicas throughout Italy. There I learned that when you’re seeing a work of art in its original setting, you get a richer sense of its provenance and significance.

The historical context, the architectural style, and the artwork reveal advancements in engineering and art, political and personal rivalries, and foreign influences.

In Florence, Brunelleschi competed with his younger contemporary Ghiberti to create bronze baptistery doors but lost. In Venice, the Byzantine mosaics and treasures of St Mark’s Basilica speak of the city’s political power and lucrative trade with the East. The surviving relics shed light on the socio-political atmosphere of their moment of creation.

Basilicas, cathedrals and churches: my selected highlights

Here are my tips for what to look out for in the main churches of Rome, Florence and Venice. I’ve also suggested some lesser-known churches worth visiting for their art, and the insights they give you into Italy’s past.

Unless you’re well-versed in Italian history, art, and architectural styles, try to visit with a guide: they’ll help you understand and enjoy what you’re looking at. Guides can also help arrange the logistics of your visit, allowing you to avoid long waits and gain exclusive access.

Churches to visit in Rome

Discover hidden details in St Peter’s Basilica

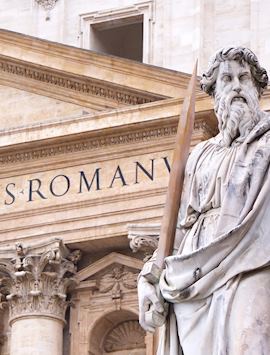

Rising up in the west of Rome, St Peter’s Basilica was built on the site where it’s thought the saint was crucified. It’s now the symbolic heart of the Roman Catholic Church. The bronze-panel doors of the basilica’s façade open to reveal a cavernous interior.

Branching off from the nave in this 187 m (615 ft) long internal space are numerous altars and side chapels filled with marble monuments. At the far end, in the apse, St Peter’s cast bronze episcopal ‘throne’ is suspended in a flamboyant baroque sculpture by Bernini.

Your gaze is drawn almost magnetically to Bernini’s baldacchino, the soaring canopy with spiral pillars that covers the papal altar, right below the basilica’s immense ribbed dome. The ceiling from Rome’s Pantheon was allegedly melted down to help create this canopy.

Taking your gaze skywards, the dome’s roof is decorated with stucco marble and paintings of figures such as the Evangelists and angels. If you crane your neck and peer right up to the top of the lantern, you’ll see a depiction of God the Father.

If you’re thinking there’s a lot to take in here, you’d be right. Whether you’re religious or not, the basilica has been deliberately designed to provoke a sense of awe.

From an art or architectural perspective, there’s a huge variety of styles to absorb. In the baldacchino, you’ll see the fluid movement and busyness of the baroque period. Elsewhere, in a side chapel as you enter, Michelangelo’s pietà embodies the Renaissance ideals of classical beauty. (A pietà is a sculpture or picture of the Virgin Mary cradling a dead Christ.) A guide is crucial here to help focus your field of vision.

Recently, even though it was my umpteenth visit, my guide was still able to point out new details. For example, there’s a stained-glass window set within the apse featuring an image of a white dove (representing the Holy Spirit), surrounded by orange and butter-yellow rays of light. In the setting, the window looks tiny and delicate, so I was surprised when my guide told me that it’s over 1.5 m (5 ft) high.

Tip: If you have time, climb to the viewing gallery of the dome. You’ll be rewarded with views stretching over the Vatican City and Rome. When you’re facing St Peter’s Square, look down to see the line-up of statues of saints crowning the basilica’s roof. Look slightly above the left-hand colonnade of the square to locate the Vatican Corridor. This passageway, running above the streets from the Vatican to the Castel Sant’Angelo fortress, was once an escape route for the popes.

See Caravaggio and Bernini masterpieces in central Rome’s churches

Whenever I’m in Rome, I always like to duck into certain churches to see their art once again — it’s like visiting old friends. All the churches I’m about to describe are centrally located, and most visitors will stroll past them unaware of the pieces inside.

In Santa Maria della Vittoria, a candlelit, out-of-the-way 17th-century church near the Via Veneto, you’ll find what I think is one of the most arresting sculptures ever created. A rare combination of marble and metalwork, Bernini’s Ecstasy of St Teresa is a startlingly sensual carving of the saint lying on a cloud, about to be pierced by an arrow from a cherubic-looking angel. It’s a great example of the high volume of emotion and drama that features in baroque art.

Tucked away in a chapel in the early Renaissance church Santa Maria del Popolo, on the north rim of Piazza del Popolo, are two paintings by Caravaggio: The Calling of St Matthew and The Crucifixion of St Peter. A stone’s throw from Piazza Navona is the 16th-century church of San Luigi dei Francesi. Behind its stone frontage is a gilded interior, but the real riches are three more Caravaggios featuring St Matthew.

What I love about all these Caravaggio paintings is how he depicts a single light source — a window or a candle — so you only see what the light falls on. You might notice, too, how some of the figures have tanned faces or hands. Caravaggio used everyday people, like farmhands, as his models — a daring, controversial act at the time.

Churches to visit in Florence

Explore ¹ó±ô´Ç°ù±ð²Ô³¦±ð’s Duomo

¹ó±ô´Ç°ù±ð²Ô³¦±ð’s Piazza del Duomo contains the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore as well as its freestanding bell tower (climb it for an excellent, close-up view of the dome) and baptistery.

Resting above an exterior of white, green and red marble, the Duomo’s enormous ocher-hued octagonal dome dominates the skyline. The baptistery has a similar exterior to the cathedral and boasts a pair of bronze doors with intricately sculpted panels. Before he went on to design the cathedral’s celebrated dome, Brunelleschi entered a competition to create the doors but famously lost out to 20-year-old Ghiberti.

The interior of the cathedral is relatively sparse, though the internal dome is a huge, heavily frescoed space depicting a nightmarish Last Judgment. Most of its artistic treasures lie in the adjoining Museo dell’Opera dell Duomo, including the original baptistery doors and Donatello’s haunting Penitent Magdalene.

A guide will help you unlock the origins and history of the Duomo complex, financed in the heyday of the Florentine Republic by a group of guildsmen rather than the clergy. This was a period of feverish competition between artists, who won commissions through their connections to high-ranking Medicis, the then-rulers of Florence, and endorsements by other leading political figures.

For me, the most intriguing (and quirky) sight in the cathedral is one of the world’s oldest functioning mechanical clocks. A local watchmaker, Angelo di Niccolo, created the mechanics in 1443 and the clock still measures the Italic hour from sunset to sunset (although it is several hours fast).

Warning: logjams of people are almost inevitable if you climb the dome. Its steep, confined stairs are not for the claustrophobic. But the views over the city’s terracotta rooftops are worth the cramped ascent.

Listen to a Gregorian chant at ¹ó±ô´Ç°ù±ð²Ô³¦±ð’s San Miniato al Monte

Florence has many lesser-known churches that are worth popping into for their art. I suggest Santa Maria de Novella for early Renaissance artist Masaccio’s trompe l’oeil fresco, Trinity.

The basilica of Santa Croce, meanwhile, is the resting place for Michelangelo, Machiavelli and Galileo, and contains some frescoes by Giotto, which were only rediscovered in the 19th century.

In Oltrarno, after a short walk uphill past the Piazza Michelangelo viewpoint, you come to the working abbey of San Miniato al Monte. When I lived in Florence, I came here to listen to the monks performing Gregorian chants inside the abbey’s Romanesque church — a tradition hundreds of years old. Chants still take place at San Miniato on weekdays, Sundays and feast days — try and attend one if you can.

Churches to visit in Venice

Learn about Venice’s backstory in St Mark’s Basilica

St Mark’s looks drastically different from other Italian basilicas you’ll see. It uses a Greek cross plan and is topped by four main domes. A surprisingly squat structure, it doesn’t punctuate the skyline the way other churches do. Your eyes are drawn to the curves of the two rows of arches over the porch, and the statues of St Mark and the winged lion (a piece of Christian iconography adopted by Venice as the Republic’s symbol). The lion stands out against a backdrop of lapis lazuli blue, speckled with gold stars. It all evokes Byzantium, rather than Italy.

When you enter, your eyes take a while to adapt to the darkness. The scent of incense sometimes hangs in the air. Then the expansive, vivid gold mosaics begin to glint. Venice, prosperous from its merchant trade with the East, assimilated oriental influences into what was originally a grandiose chapel for its Doges (elected leaders), later a cathedral. St Mark’s was intended to signal to the world the growing might of the Venetian Republic.

Guides can show you highlights from the basilica’s plundered booty from the East — including the body of St Mark (one mosaic depicts how the Venetians stole his relics from Alexandria). Other treasures include Byzantine icons and, more famously, replicas of the quadriga, four gilded bronze horses pillaged from Constantinople’s Hippodrome in 1204. The original statues are now kept in the basilica’s museum. They did leave Venice when Napoleon spirited them away to Paris in 1797, but were returned 18 years later.

Visit some of Venice’s out-of-the-way churches

Aim to get lost in Venice — at some point you’ll inevitably wander into a modest backstreet campo (square) whose church contains noteworthy art. One example is the church of the Angelo Raffaele (Raphael) in the quiet residential district of Dorsoduro, across the Grand Canal to the west of St Mark’s. It has some lively frescoes by Guardi.

Standing at the water’s edge of St Mark’s Square, you see the bulging dome of Santa Maria Salute across the entrance of the Grand Canal. This church was built to celebrate Venice’s deliverance from a plague in the 17th century. Worshipers still gather there to give thanks annually. Its dim interior contains Renaissance artist Tintoretto’s Wedding at Cana (which features a self-portrait).

Admirers of Renaissance art can also visit the Gothic church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari (simply known as ‘I Frari’). Titian’s bold, eloquent Assumption of the Virgin hangs above the high altar.

If the style of St Mark’s appeals to you, cross the lagoon to reach the sleepy, half-forgotten island of Torcello. Its Byzantine cathedral contains fine golden mosaics.

A note on terminology — basilica vs cathedral vs duomo

Whereas a cathedral is the principal church of a diocese, a basilica is a church that has been given special privileges by the Pope. Architecturally, basilicas are derivative of early Greek and Roman buildings: square-shaped, with lots of columns and a side aisle. Duomo is an Italian word for cathedral.

Best time of day to visit Italy’s basilicas, cathedrals and churches

In general, get to Italy’s places of worship early in the morning, as they open, to avoid the crowds. However, it’s worth checking the times of mass, as during services access to certain areas of a church may be closed off. During the Italian summer, it can also be pleasant to visit churches at midday and take refuge in their cool interiors.

If you’re planning on climbing domes or bell towers, try to do so toward the end of the day. You may get a glimpse of these spaces when they’re near empty. The views are arguably better, too, in the softer early evening light.

Dress code in Italy’s churches

As a general guide, both men and women are required to cover their shoulders and arms, and their legs from the knees down.

Entry fees

Be prepared, in Venice especially, to have to pay to visit some churches, or to view certain artworks inside.

Start planning your trip to Italy's art cities

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Italy