With the Himalaya spanning ten Indian states in the north, and the hills of the Western Ghats to the south, India presents many possibilities for a walking vacation. As many visitors to the Indian Subcontinent are drawn to Nepal’s well-known routes, you’re likely to find the trails quieter and the guides attentive. Routes range from gentle tea-plantation strolls to multiple-day treks.

India’s walking routes

The Northeastern Himalaya

Walked by India specialist Graham

India’s little patch of northeastern Himalaya is squeezed in-between Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet. The northernmost section is the state of Sikkim, an independent kingdom until 1975 that almost made me forget I was in India. Its network of well-worn walking trails pass a conglomeration of Hindu shrines, Buddhist monasteries, Nepalese food stalls and Bhutanese architecture which give the area an atmosphere all of its own.

West Bengal is a sprawling state that runs from Sikkim, down the west of Bangladesh, to Calcutta and the coast. The state has absorbed Sikkim’s multicultural influences, as well as the colonial legacy of British rule. The hill station of Darjeeling encapsulates this best, where British bookshops trade next to Tibetan craft stalls.

Take a tour through Kalimpong’s villages

Fields of sky-blue poppies and peach-pink roses: Kalimpong is easy to distinguish from nearby towns. The town’s temperate climate is ideal for growing flowers, which has turned it into an important trading post on the border of Sikkim and West Bengal.

Despite its thriving bazaar, Kalimpong has grown little, and most of the population live in hamlets in the surrounding hills. I joined a guide from the Mondo Foundation, a charity supporting rural Himalayan communities, to take a walk through these small communities. An extensive network of trails links the villages, making it simple to tailor the walk to your fitness levels or, in our case, duck out of a rain shower.

Following narrow paths, we squeezed between houses and past gardens. Zigzagging upward, the views out across the Himalaya got bigger and bigger — Kanchenjunga (India’s highest peak) towers above on a clear day. We stopped for lunch in a settlement of about ten houses, stooping to enter a wooden-framed house where I was served a bowl of gently spiced dhal and rice. You can lengthen your walk and stay the night here, in a basic but clean room with an outside toilet.

My guide then explained that it was his son’s coming-of-age ceremony that day, a tradition for boys turning 12. Walking on to his family home, we were greeted by a table covered in food and his entire extended family. English isn’t spoken up here, but my guide translated for me (mainly so I could pass on my compliments to the cooks).

After finishing the walk back in Kalimpong, I settled into the Orchid Retreat, a family-run guesthouse, for the night. You stay in small cottages in the back garden, built around the greenhouses that supply the property’s flower business. The surrounding garden is a wild tangle of exotic plants and flowers.

Stroll through tea fields at Glenburn Tea Estate

An hour’s bumpy drive outside Darjeeling is Glenburn Tea Estate. Built by 19th-century Scottish tea planters, the estate still thrives — albeit now in the hands of an Indian family. The original planters’ bungalows have been renovated into pastel-painted suites with four-poster beds.

The Darjeeling area has few roads, with local residents relying on the network of trails that winds through tea plantations and surrounding villages. Staying at Glenburn, you can stroll through the tea fields or arrange a longer, guided hike.

I chose an early morning walk from my bungalow, down to the River Rangeet. We left at dusk, my guide leading me through the slender tea plantation paths, carved out by years of tea pickers’ footsteps. We passed through a village where the plantation staff live, and the morning chores were underway. A couple of hours later we arrived by the riverside. The estate has a small wooden lodge here, from where I sat and enjoyed a breakfast of freshly cooked eggs before being driven back up to my room.

Later my guide and I tackled a walk uphill to a local village north of Darjeeling. With guides on-hand daily at Glenburn, you can pick and choose your itinerary, being as active as you wish.

A rewarding hike is the five-hour walk to Darjeeling town. Passing through a number of tea estates and forested areas, you’ll also happen upon the Buddha of Badamtam, a 4.2 m (14 ft) high bronze statue built on a viewpoint that looks out across the snow-covered Himalaya. In Darjeeling town you can enjoy a well-earned lunch before being driven back to Glenburn.

How to get to the northeastern Himalaya

The region is best reached by a short domestic flight into Bagdogra, the closest airport (direct flights run from Calcutta and Delhi). It’s then a four-hour drive into the hills to Darjeeling, and a farther four hours to Kalimpong.

The Himalayan Foothills

Walked by India specialist Rowena

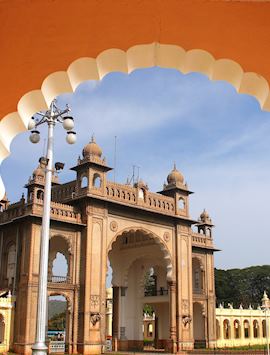

Arriving in the Western Foothills, I was keen to explore the Golden Temple in Amritsar and the Aarti ceremonies on the riverside ghats of Haridwar. I actually spent more time in the Shivalik Hills, better known as the foothills, which rise up between these cities, creating steep valleys and canyons. They’re streaked with a huge network of footpaths, where routes wind through subtropical pines and broadleaf forests to rocky peaks above.

Stay in local village houses in Almora

A few years ago, the residents of Almora, a small district in the foothills northeast of Delhi, saved up to buy a road to make it easier for the outside world to reach them. The journey there from Delhi still involves a five-hour train ride to Kathgodam (the nearest station), followed by a four-hour drive and a half-hour walk past well-tended smallholdings and pine trees.

Almora is a rural area peppered with small villages and a few hotels. The lack of hotels has created a niche for local homeowners, who offer their houses as places to stay. The Itmenaan Estate runs four-night walks through the region, with stays in local homes along the way. The houses only have two rooms — one for two adults, another for the guide — so you’ll rarely meet another visitor.

The first night is spent in the main lodge, a 100-year-old stone house, before setting off on foot. The network of footpaths is so extensive that your guide can tailor the day’s walk to your interests or fitness levels. My guide and I set off along a narrow track, the terraced fields below us planted with grains and vegetables.

Walking about five hours each day, we strode through rhododendron fields, their fuchsia buds just beginning to peek out of the undergrowth. Passing a local school, my guide persuaded me to pop in to say hello. The entire class, all six of them, were eager to meet me and led me to their world map to point out where I’d come from. We frequently passed neatly dressed school children walking — in a journey that usually takes hours — to these tiny village schools.

The village houses have no hot water (they’ll boil up a bucket for you) or electricity, but there’s a big, soft bed and a hot water bottle waiting at the end of each day. The house at Thikalna village has a 180-degree view of the snow-topped Himalaya. In the evenings your host for the night will serve a vegetarian curry — all meals are included — outside, and watch the sun set behind the peaks.

Routes usually finish back at the main lodge, from where you can travel back to Delhi or head farther north to Corbett National Park, renowned for its birdlife including the rare ibisbill.

Learn about Tibetan culture in McLeodganj

If you’d rather stay somewhere less remote, or explore in your downtime, you can opt to stay in a Himalayan town. Dharamshala, in the northern foothills, is a busy gathering of shops, markets and cafĂ©s. Upper Dharamshala, known as McLeodganj, is home to the Dalai Lama and a growing community of Tibetan Buddhists. Barefoot monks walk the streets in red robes, bright prayer flags flicker in the wind and you’ll be welcomed with the polite, untranslatable Tibetan greeting ‘tashi delek’.

There’s a variety of routes in the region to pick from. For a gentle ramble, walk along a pine-lined path to Saint John in the Wilderness, an hour outside the town. A Gothic stone church, it’s the resting place of the British who were killed in a nearby earthquake in 1905.

A more challenging walk takes you up to Triund, a spring-green alpine meadow atop a flat ridge. It’s a steep, four-hour climb, passing through oak and deodar forests, remote homesteads and farmland. Climbing to 2,975 m (9,760 ft), you emerge onto the ridge with the Kangra Valley dropping sharply down on one side. The other edge of the ridge overlooks the Dhauladhar range (literally translated as the white range), a steep granite chain of mountains named after their almost permanent covering of snow.

After a day’s walk, you can enjoy dinner at one of the local eateries. The tiny Norling Restaurant makes subtly spiced chicken momos (Tibetan dumplings). Handicraft stalls line the streets, selling vibrantly dyed handloom fabrics, woolen gloves and rolls of prayer flags.

The main focus of the town is the Tsuglagkhang Complex, the Dalai Lama’s official residence, as well as a monastery and museum. Visit at dusk and you might catch the evening prayers at the monastery temple. The Tibetan Museum tells harrowing tales of Tibetan refugees walking through the Himalayan pass to India after China’s occupation of Tibet in 1950, and volunteers will often share their first-hand experiences.

The Western Ghats

Walked by India specialist Hannah

Older than the Himalaya, the Western Ghats are so biologically diverse they’ve been awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status. Stretching from the north of Mumbai to the southern state of Tamil Nadu, they host over 500 bird species and more than 7,400 kinds of flowering plant — and scientists are still logging hundreds of unclassified species.

The British built hill stations up here to escape the sticky heat of the plains below, and I found the cooler temperatures and gentle breeze an ideal walking climate. You can take leisurely ambles through forests or day-long walks up to some of the highest tea fields in the world.

Munnar: a British hill station

On the four-hour drive from Cochin to Munnar, the scenery just kept getting greener, until the car was driving through an emerald landscape of manicured tea bushes. Centrally located, the former British hill station of Munnar is a good base for exploring the Western Ghats. Spice Tree, a boutique hotel about an hour from the main town, is a good choice for walkers, with many routes starting from the hotel door.

As is typical of India, the guides are completely flexible and able to conjure up a route that fits the duration you were thinking of in a moment’s notice. I’d been told the typography of the Western Ghats creates some remarkable sunrises, so my guide woke me early one morning for an hour’s walk to a nearby viewpoint. As the sun began to ascend, it illuminated a shelf of mist that had collected in the valley below, the peaks of the hills poking through like little islands.

To learn more about the history of the area, I also embarked on a more challenging walk through the Kanan Devan Hills. To make the route a little easier, my guide and I were driven about half an hour from the hotel to a convenient starting point. Initially walking through tea plantations and local villages, we soon began to encounter dense shola forests and jagged mountain ridges. As the forests cleared, we walked through flatter shola grass meadows with views across the Western Ghats.

As we walked, my guide explained how chests of tea were once transported to Top Station, the final stop on the Kundali Railway. They would have been conveyed 5 km (3 miles) down a steep cliff by ropeway, before being moved onward by cart. The railways and ropeway has since been disbanded, with the remaining relics now at Munnar Tea Museum. But, as we reached Top Station at an altitude of 1,700 m (5,577 ft), I could appreciate the difficulty of this logistical feat and the ingenuity of the solution.

Start planning your trip to India

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in IndiaFurther reading

- What to do in India: our highlights guide

- India to Nepal: where to go in the Himalaya

- Touring India’s Golden Triangle

- Luxury rail journeys through India

- What to do in Kerala: our highlights guide

- India’s western foothills

- Family vacations in India

- India’s toy trains: Shimla, Darjeeling and Ooty