By Jordan specialist Nick

Both instantly familiar and ultimately mysterious, Petra was the capital of one of the biggest and richest kingdoms in the ancient world. Despite that, there is much we don’t know about the people who once lived here.

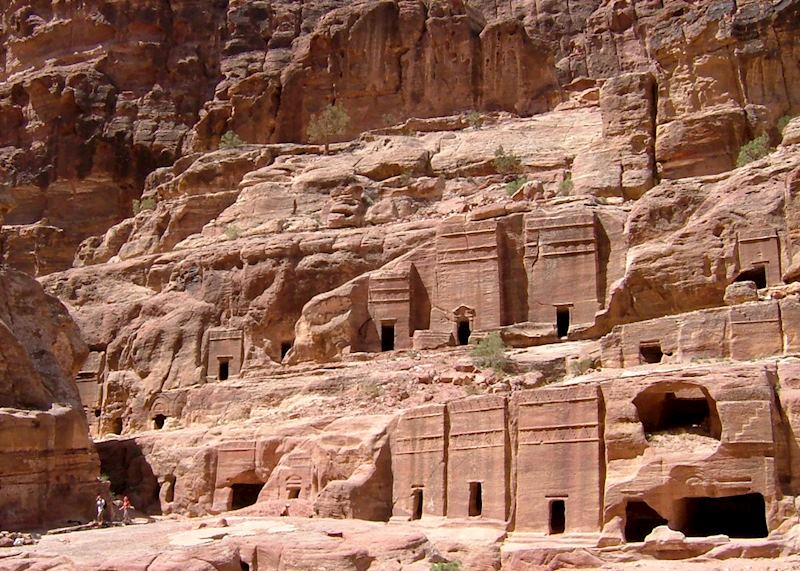

It’s literally a hidden city, tucked into a narrow wadi and almost impossible to see until you’re inside. There, you’ll find dozens of Greco-Roman-style tombs chiselled into the rough red-sandstone cliffs, impressive in their size and artistry even today. The sprawling and concealed nature of this UNESCO World Heritage Site can make Petra feel overwhelming, so I’ve written a guide to help you plan your visit.

How long to spend at Petra

To be honest, I could spend a week or more there, just wandering through the canyons, exploring the site. Whether you’re doing a weeklong tour of the country or adding a Jordan jaunt onto a visit to Egypt or Jerusalem, I suggest spending a minimum three nights and two full days at Petra.

It’s a long drive from Amman, but you can travel along the 5,000 year old King's Highway, stopping to see Mount Nebo, with its views over the Dead Sea as well as the Christian mosaics of Madaba and the crusader castle of Kerak. You’ll arrive in the middle of the afternoon. I advise going to sleep early for a pre-dawn start — Petra is open sunrise to sunset and it’s particularly photogenic in the early morning light.

If you’d like an introduction to the site, a two-hour tour with a private guide offers plenty of insight and history. After that, I like to wander on my own. The paths are clearly marked and the Petra Visitor Centre offers good maps in various languages, so you can freely explore the city at your own pace.

What to see in Petra

Time, sand and tectonic activities have damaged Petra, but much remains remarkably intact. The city is carved directly into the living rock, the Hellenic-style buildings precisely chiselled out of the red sandstone.

Like their Egyptian contemporaries, the Nabataeans put great weight on the importance of the afterlife. You’ll see tombs that are much larger and more elaborate than the daily living quarters. Temples are dedicated to a varied pantheon that shows the influences of both the Greeks and the Egyptians, with goddesses who closely resemble Isis and Aphrodite.

The Siq

The first time I visited Petra, I entered the Siq at dawn. The warm light of sunrise made the sandstone come alive with shifting shades of rose, gold and ochre. In the early morning hush, I was one of just a handful of initial visitors.

It’s a long and winding way, almost a mile, before you reach the city proper, walking between cliffs that can reach heights of 182 m (600 feet). You’ll pass remnants that offer hints of the Nabataean culture — niches for long-gone statues, a small temple off to one side and the remains of 2,000-year-old terracotta pipes used to bring water into the desert city. Resist the urge to rush through and you’ll be rewarded with a more complete understanding of the Nabataean sense of drama.

This narrow crack isn’t technically a canyon or gorge — instead, it’s a split in the massive slab of rock caused by an earthquake. You can see where the striations match on either side. It meanders and narrows, sometimes squeezing down to just 3 m (10 feet) wide. Using this as an entrance allowed the kingdom to defend the rich city easily, as well as providing a ceremonial procession route that heightened anticipation, both then and now.

In the evening, you’ll leave the city through the Siq, the ebbing light bringing out hints of violet and maroon in the stone.

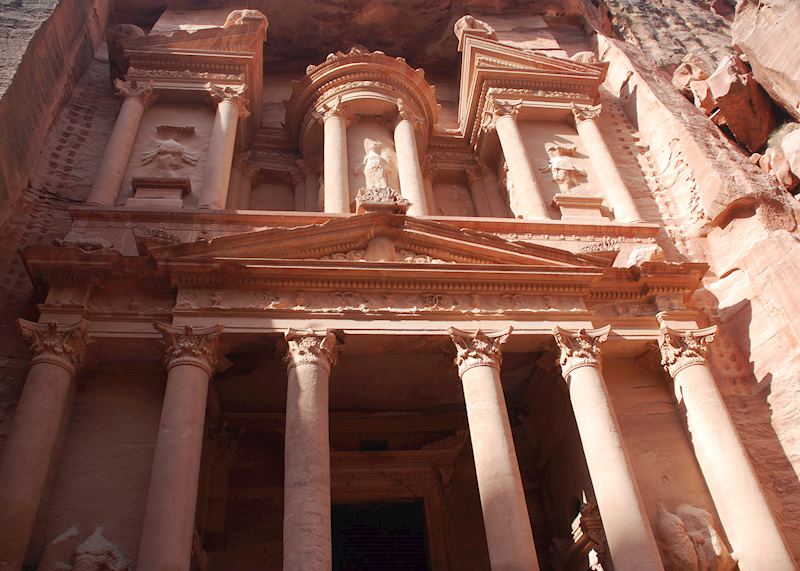

Treasury

As you emerge from the shaded interior of the Siq into the blazing sun of Petra proper, you see the Treasury — a perfectly symmetrical Hellenic-style tomb carved into the rough, red cliff face. Its split pediment and soaring columns are well known from countless images, as well as its starring role in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Despite its familiarity and the fact that I’ve visited multiple times, I’m still rocked back on my heels by the wondrously incongruous beauty of it.

The Arabic name is Al Khazneh, a translation of ‘Treasury’. The name comes from a relatively modern misapprehension that a great pharaoh once hid his wealth here, guarded by clever booby traps. If you look closely, you can see bullet holes that date back to the 18th century, where greedy (but cautious) looters tried to trigger any traps before they entered to claim their imagined prize. In fact, it was never a treasury but the tomb of King Aretas III, and later probably used as a temple.

Despite the strongly Greco-Roman influence, the architecture of the tomb is a synthesis of styles from around the world. Nabataeans borrowed liberally from other cultures, and on the Treasury (and throughout the city) you’ll find elements that hint of far-away places.

The elaborate façade opens to a shadowy and bare interior. Millennia of looting have left the Treasury — and most tombs in the city — wholly empty.

The Street of Façades, the Temple and the Royal Tombs

Beyond the Treasury, you’ll find a row of tombs with tall, impressive façades, some quite high on the cliff face. Floods and looting have damaged some and filled others almost entirely with mud. Farther down, there are smaller tombs, presumably for those without the means for more grandiose graves.

Past that, the thoroughfare opens up and you come to the Theatre, a massive semi-circular stadium scraped out of the cliffs. It’s a later addition, and the Nabataeans had to carve through some already existing tombs to create it. Romans enlarged it in the 2nd century, until it could hold 8,500 people — approximately one third of the city’s population. An earthquake damaged it and parts were scavenged for other building projects, but I remain impressed nonetheless.

After the Theatre, the wadi widens further and you approach the Royal Tombs. This elaborate row includes some of the most striking tombs in Petra, and I suggest you take your time here.

Monastery

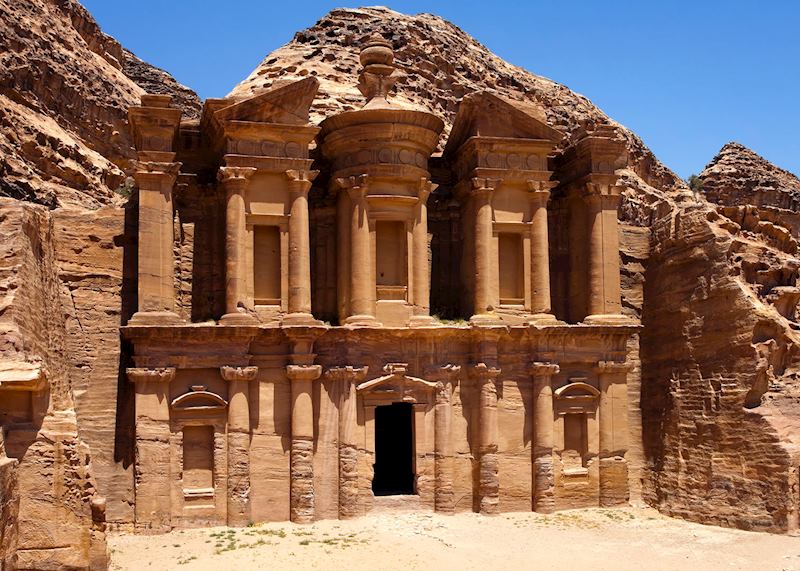

High on the cliffs of Petra is the so-called Monastery. You’ll have to walk up more than 800 rock-cut steps to reach here and it can be a bit daunting, but there are tea tents where you can pause on your way up. You can also make the climb easier by starting in mid-afternoon, when the stairs are in shade. This has the happy effect of putting you at the top at the time of day when the slant of the sun brings the detailed carvings to life.

At the top, you’ll find an enormous tomb, with some stylistic cues that are similar to the Treasury — an urn in a split pediment and capital-topped columns — but much larger. The façade soars 50 m (164 ft) high, and the vast, echoing interior is lit only by the light that streams through the yawning 8 m (26 ft) high doorway. The building is faced by a large, open plaza, where sacred ceremonies were possibly held.

As with many of the names in Petra, the label ‘Monastery’ is thought to come from a misunderstanding. There are crosses carved on the walls inside, hinting at a latter-day use as a Christian church, perhaps during the Byzantine era.

Opposite the Monastery is a tea shop in a cave, a shaded sanctuary where you can cool off after your climb and admire the details of the sandstone sculpture in the warm sun of late afternoon.

High Place of Sacrifice

The long, fairly steep route to this site is thought to have been a processional way, climbed by priests on their way to perform a sacred sacrifice.

Hints remain of the route’s ceremonial role, including two towering obelisks that were carved from the stone. I find it mind-boggling to contemplate the sheer volume of stone that must have been carved away to create these two monumental pylons, which each stand 6 m (20 ft) high.

After all that climbing, you’ll reach an area with an altar. The carving here seems rougher or more weathered than the pristine examples below, but it’s still easy to make out the grooves carved to carry away the blood from the sacrificial animals, a literally visceral remnant of the Nabataean religion.

High above the city, you get an inkling of why the Nabataeans held their sacred events here. You seem close to the heavens. Looking down, the monumental buildings, milling crowds and lumbering camels are reduced to toy-size by the distance.

What to pack when visiting Petra

When visiting the Middle East, I usually suggest keeping limbs covered and dressing with a certain degree of modesty — this is a conservative part of the world. But in Petra, those rules don’t apply. Pack for comfort, keeping in mind that you’ll be hiking over rough terrain in a hot, dry climate.

You’ll be walking over lightly sandy ground, uneven rocks and gravel, so sturdy boots are a must.

Where to stay in Petra

Frankly, when you visit Petra, you’re there for the city, not the hotels. You can expect a clean and comfortable place to rest after a long day hiking through the city, but nothing particularly indulgent.

Just a very short walk from the opening of the Siq is Mövenpick Resort Petra. You’ll find spacious rooms and a pool, as well as a central atrium dotted with palm trees and bordered by a colonnade. Farther away, the Petra Marriott offers a comfortable stay with exceptional views over the area’s dramatic scenery. (Petra, being hidden in the wadi, isn’t visible.) Like most hotels, the Marriott offers a shuttle to the entrance of the Siq.

A less-expensive option is the Petra Guest House, which provides a clean, basic place to stay just steps from the entrance to the city. The hotel’s Cave Bar, set in an actual cave, is probably the city’s best locale for a quiet drink in the evenings.

History of Petra

Established in about the 3rd century BC, Petra was a thriving city in a sprawling kingdom until the Byzantine era. Wealthy and cosmopolitan, the Nabataeans leveraged their central position to create the massive trading system that was the basis for their economy.

For centuries, the capital was the hub of a network of caravans from Africa, Asia, Arabia and the Mediterranean, carrying frankincense and myrrh, silk and silver, spices and slaves, jewels and gold. When the kingdom was annexed by the Romans in the 1st century AD, its wealth only increased as it tapped into the empire’s larger trade routes.

Nabataean engineers used a sophisticated system of dams, cisterns and irrigation to support a huge population in the middle of a desert — far more people live there today. This innovative hydro engineering, combined with Petra’s exceptionally defensible position, made it a long-lived and stable kingdom, which only faltered when the Roman Empire began to shrink.

Eventually, a series of earthquakes destroyed many of the freestanding buildings. By the time Islamic armies invaded in the 7th century, Petra was largely deserted apart from a lingering Bedouin community.

Inspired by stories and myth, Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt paid local tribesmen to take him to Petra, reintroducing the so-called lost city to the larger world in 1812. Careful archaeological exploration only dates back to 1958 and continues to this day.

Read more about trips to Jordan

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Jordan