By Liz

The sun-warmed valleys of the Garonne and Dordogne rivers produce some of the world’s most prestigious wines. But, there’s more to this fertile swathe of southern France than just vineyards and wine tastings. Along the riverbanks, and in the countryside, you’ll find medieval villages, historic chateaux and regional cuisine that spotlights duck, goat’s cheese and mushrooms.

The limestone cliffs and hills of the Dordogne Valley are also home to vast cave complexes, where you can still see sophisticated works of art drawn on stone walls with primitive pigments, dating back to the very dawn of humanity.

Beyond the big names — wines in Bordeaux and Saint-Émilion

Straddling a bend on the Garonne River, the city of Bordeaux has been the heart of a wine region since the Middle Ages. You can see it in the very architecture of the city — historic buildings along the river have wide doors and gentle ramps for moving barrels down to waiting boats.

Bordeaux’s historic downtown has been recently renovated, and I suggest allotting at least a day to enjoy the glories of its 18th-century architecture and world-renowned food.

As compelling as the city is, I visit the region for its wines. One of France’s largest appellations, its sunlit vineyards create some of the most storied (and expensive) wines in the world, including Dauzac, Lafite Rothschild and Margaux, all located in the Médoc region.

A driving tour offers you a well-curated glimpse at the inner workings of some of these celebrated houses and the production process. If you prefer a more intimate insight into the Bordeaux wines, I suggest you take a private blending class.

Boasting a tousled mane of blond hair and an infectious smile, Rémy is a trained sommelier who was born in Bordeaux. His passion for the region’s wines comes through in every gesture and word. His class begins with a refresher on the familiar rituals of wine tasting, as well as an introduction to the area’s history of wine production and the regions inside the Bordeaux appellation.

Then he launches into an explanation of the eponymous Bordeaux blend and how cabernet sauvignon’s tannins are mellowed by the fruity notes of the merlot. We discussed my preference for big reds and grippy, bold tannins.

Next, using a tall graduated beaker, you begin to sample different ratios — 70% cabernet sauvignon was too much for me, but an equal mix was insufficient. I settled on just 35% merlot, which Rémy put into a demi bottle for me and labelled with my name.

For a different but equally intimate look at the region’s vineyards, you can also take a bicycle tour of Saint-Émilion, a small appellation on the ‘right bank’ of the Garonne. Here, the chateaux are smaller than the grand Médoc houses, so as not to waste any land that could be growing grapes. Some fields are planted with merlot and cabernet franc and cultivated with horses instead of tractors, to help protect the soil’s delicate substrate.

The roads are narrow and sleepy, with few cars, so I felt perfectly safe as my guide, Mikael, led me past rows of green vines flourishing in the spring sunlight. Irrigation is forbidden here, if vintners want the coveted Grand Cru or Premier Grand Cru classification, so the air was slightly hazy where the horses had kicked up dust.

We stopped at a small winery, run by the same family for four centuries, and I met the three generations who live there now. In the cool dark of the cellar, an apprentice sommelier showed off a 400-year-old bottle from the winery’s earliest days, and we sampled several (much more recent) vintages.

Mammoths, rhinos and aurochs — cave art in the Dordogne

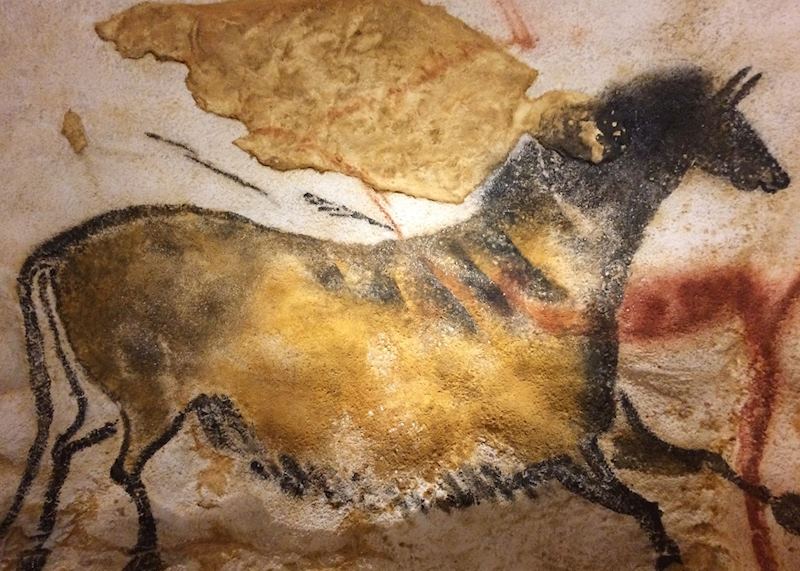

Some of the world’s best-known cave art is from the Grotte de Lascaux, where a herd of aurochs seems to gallop silently across the rippling stone walls, their outlines remarkably lifelike and full of suggested motion. The art, which dates back about 17,000 years, was discovered in the 1940s but the caves have been closed to the public since 1963.

Today, you can visit a remarkably accurate replica of the site, commonly referred to as Lascaux IV. Chilly, damp and slightly eerie, its authenticity is only slightly undermined by the number of visitors. A comprehensive museum exhibit helps to shine a light on what we know about the lives and culture of early humans.

To walk through caves where our ancestors lived and see their original art with your own eyes, I suggest you visit Rouffignac Cave, a 30-minute drive to the west. To enter the cave, you’ll board a small train with your guide and a small group to chug down into a dense, enveloping darkness. Light damages the artwork, so the only illumination comes from a single flashlight, held by the guide.

The single, wavering beam of light gave me an idea what these drawings must have looked like to the artist, who saw them by the dancing light of an oil lamp. A procession of woolly mammoths lumbered along the wall, their outlines overlapped by drawings of rhinos and ibexes. The light also picked out deep parallel gouges, thought to have been made by an ancient cave bear.

Pech-Merle Cave, 90 minutes south, displays the usual mammoth and ibex figures, as well as a negative impression of a human hand outlined in a cloud of red ochre. The sight of the small handprint drew me up short. More than any other piece of cave art, this seemed like a tangible link to people who lived almost 27,000 years ago.

Visits to Rouffignac and Pech-Merle are severely restricted, to help preserve the delicate pigments, and there’s a good chance that one or both will close to the public within my lifetime.

Pilgrims and jazz music — the Dordogne’s villages and chateaux

Lying an hour south of Pech-Merle, Rocamadour is a medieval village carved directly into a sheer stone cliff. It was (and remains) a place of pilgrimage on the Compostelle Route, and it has drawn the likes of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II, as well as thousands of less-exalted pilgrims. Supplicants still come today, and you can sometimes see them on their knees, laboriously climbing the well-worn stairs to the city’s many sanctuaries.

But most visitors are here to appreciate the centuries-old buildings and the views over the green valley. It’s a good place to stop for lunch and perhaps buy some leather shoes, a traditional purchase here. Pilgrims often wore their soles out on their long walk and arrived in need of new shoes.

The Dordogne’s banks are also dotted with dozens of chateaux, their crenellated silhouettes still dominating the landscape after centuries. The best preserved of these is Château de Castelnaud, a 13th-century fortress with massive ramparts that sits on a clifftop overlooking the Dordogne and acted as a Plantagenet stronghold in the Hundred Years’ War.

Though it’s less elegant than the area’s later turreted castles, the chateau revels in the high pageantry of the Middle Ages. You can see working trebuchets fling stones, watch a falconry demonstration and try on a gleaming helmet and cuirass.

Just down the river, Château de Beynac (whose occupants were fiercely French) seems to glower upriver at its English counterpart. The chateau’s interior is less interesting, but it looms over Beynac, arguably the region’s most picturesque village. Scenes from Chocolat were filmed here, amid the stone houses that stand shoulder to shoulder along the steep cobbled lanes. You can see both chateaux, as well as some of the region’s villages, on a driving tour through the region.

Canoeing down the Dordogne

Once a vital route for trade and armies, the Dordogne is a tame, shallow river that moves slowly but steadily toward the Atlantic. Its clear, clean waters are barely hip high at the deepest point, making it a prime destination for canoeing.

We can arrange for you to pick up a canoe and paddle down the river, letting the current do most of the work. Sheer limestone cliffs rear up along the length of the river, and you’ll see the area’s chateaux and villages from a new perspective.

You can pack a picnic (and camera) in a provided watertight compartment and pause on a pebbly stretch of the riverbank for an alfresco lunch. Or, instead, stop at one of the restaurants in La Roque-Gageac, a village built into the cliff face.

At the end of the route, a van will be waiting to pick you up. The low-effort trip is particularly popular in the hot months of July and August, but it’s less busy in June and September.

A regional cooking class in the Dordogne

Tucked behind a stone wall overgrown with honeysuckle, Ian’s house is built from warm, golden stone and has bright-blue shutters. Wearing a chef’s jacket and sporting a neatly trimmed beard, he looks very much the part of a French chef, but his accent is clearly from across the English Channel.

When I arrived at his house for a cooking class, he explained that he used to work at a bustling British gastropub but didn’t like the frenetic pace. So, he moved here, to the sleepy Dordogne countryside. The lady next door introduced him to the region’s cuisine, showing him how to prepare food in a traditional manner.

Ian’s class begins with a trip to the weekly market to buy some of the region’s local produce, grown in the same fertile soil that produces such excellent wine.

Then, back at his home, you work under his enthusiastic tutelage to create your meal. I made a goat’s cheese tartlet that was dressed with garlicky olive oil, as a starter, and a deconstructed duck confit with mushrooms and crunchy shreds of duck meat, fried until crispy in golden fat.

My class ended with a molten chocolate walnut cake, topped with balsamic-glazed strawberries and a dollop of fresh whipped cream, barely sweetened.